Problems with AI-generated information.

- Meri Shakhzadeyan

- Feb 22, 2025

- 8 min read

Updated: Feb 28, 2025

Abstract

This article explores the integration of thematic analysis with desk research to understand how individuals perceive and interact with AI-enabled misinformation. Psychological and behavioral economics theories offer a framework for understanding user behaviors and vulnerabilities in the digital age. The study highlights the importance of education, media literacy, and collaborative approaches to mitigate the risks of AI-driven misinformation. This work aims to provide insights into how we can empower users to critically evaluate content and develop effective strategies to combat misinformation in a world increasingly influenced by AI technologies.

Keywords: AI, misinformation, media literacy, behavioral economics, education, trust

Introduction

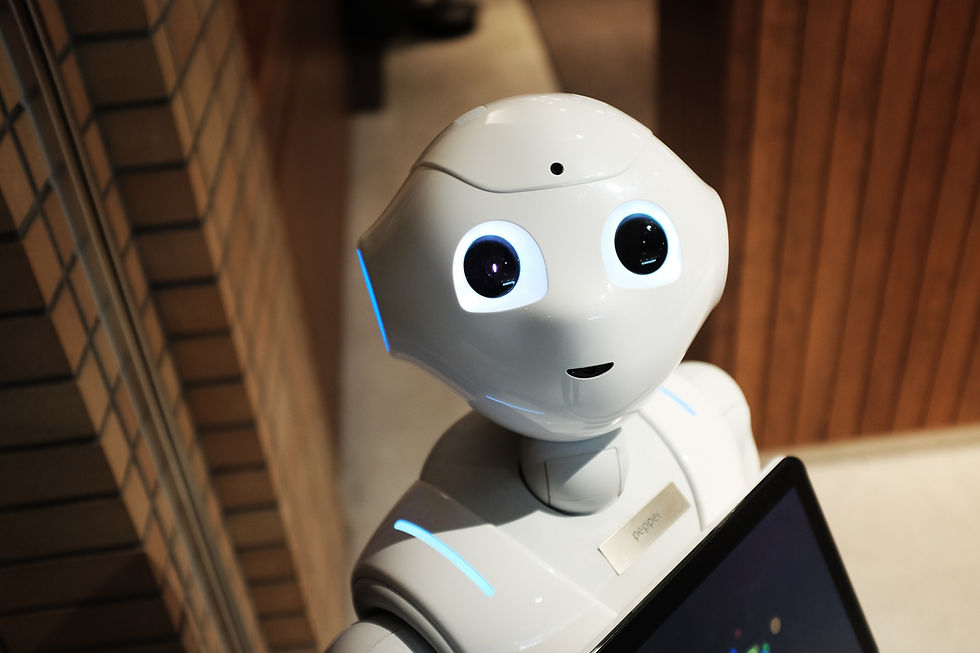

The rise of artificial intelligence (AI) has brought with it numerous advantages, from enhancing efficiency and productivity to solving complex problems. However, this same technology has introduced new challenges, particularly in the realm of misinformation. AI's ability to generate hyper-realistic content, including text, images, and video, has blurred the lines between fact and fiction. Misinformation, previously confined to human interaction, now spreads faster and more convincingly due to the sophisticated algorithms that power AI.

The creation of deep fakes, manipulated images, and text-based misinformation often goes unnoticed by the average consumer, who may not have the tools or knowledge to distinguish AI-generated content from legitimate sources. As a result, combating AI-driven misinformation has become a pressing concern for policymakers, educators, and technology developers alike.

This article investigates the nature of AI misinformation, explores the psychological and behavioral factors that make users vulnerable to it, and proposes habits-focused strategies for mitigating its effects. By leveraging interdisciplinary theories from psychology, behavioral economics, and media literacy, this paper seeks to outline a comprehensive approach to combating AI misinformation.

Thematic Analysis and Desk Research Approach

To understand how individuals, interact with AI-generated misinformation, a thematic analysis was conducted. This analysis is complemented by desk research, which includes a review of academic literature, media reports, and existing surveys on public perceptions of AI and misinformation. By combining these two methods, the article provides a multifaceted view of the problem.

User Perception of AI-Generated Misinformation

One of the key findings of this research is that many users lack awareness of how AI can manipulate information. Studies have shown that even when people are aware of the potential for AI to create false content, they tend to underestimate its sophistication. This lack of awareness often results in the uncritical consumption and sharing of AI-generated misinformation.

Additionally, the research found that individuals often assume that content from reputable sources is accurate, even when it is manipulated by AI. This is due in part to a phenomenon known as the illusory truth effect, in which repeated exposure to false information leads individuals to believe it to be true (Begg, Anas, & Farinacci, 1992). AI technologies exacerbate this effect by generating content that appears highly credible, making it more difficult for individuals to discern the truth.

Psychological Mechanisms and Biases

Several psychological mechanisms contribute to the spread of AI misinformation. One key factor is confirmation bias, the tendency for individuals to seek out information that aligns with their preexisting beliefs (Nickerson, 1998). AI-driven misinformation often targets this bias, reinforcing existing viewpoints and making it more likely for individuals to accept false information without question.

Another psychological factor is overconfidence, where individuals believe they are less susceptible to misinformation than others. This effect, known as the third-person effect (Davison, 1983), leads people to underestimate their vulnerability to manipulation. AI’s ability to generate convincing content, often tailored to an individual's preferences, makes it easier for misinformation to slip through the cracks unnoticed.

The Role of Media Literacy in Combating Misinformation

Media literacy is a key tool in combating AI misinformation. Media literacy refers to the ability to access, analyze, evaluate, and create media in various forms. In the context of AI misinformation, media literacy involves teaching individuals to recognize AI-generated content and understand the potential for manipulation.

Importance of Education

The importance of education cannot be overstated in the fight against misinformation. Education systems worldwide must integrate media literacy into their curricula. This includes not only understanding traditional forms of media but also recognizing and critically evaluating AI-generated content. For instance, students could be taught how to spot inconsistencies in AI-generated text or how to verify the authenticity of online images using tools like reverse image search or AI-based detection algorithms.

In addition to formal education, public awareness campaigns can help individuals understand the risks of AI-driven misinformation. By equipping the public with the tools and knowledge to critically engage with online content, it becomes more difficult for misinformation to thrive.

Developing Critical Thinking Skills

One of the most effective ways to combat misinformation is by fostering critical thinking. Critical thinking encourages individuals to question sources, motives, and the credibility of the information they encounter. By encouraging users to ask questions like, "Who is behind this information?" and "What evidence supports this claim?", we can reduce the likelihood of individuals accepting misinformation at face value.

Critical thinking also involves recognizing cognitive biases and heuristics that may lead individuals to make snap judgments. For instance, the availability heuristic (Tversky & Kahneman, 1973) leads people to believe that information that is easily recalled or familiar is more likely to be true. Educating people about these cognitive shortcuts and how they affect decision-making is crucial for mitigating the impact of AI misinformation.

Behavioral Economics Insights on Misinformation

Behavioral economics offers valuable insights into how individuals process and respond to misinformation. Traditional economic models assume that individuals make rational decisions based on complete information. However, behavioral economics acknowledges that people often rely on shortcuts, or heuristics, to make decisions under uncertainty.

These heuristics can make individuals more susceptible to misinformation. For instance, the anchoring effect (Tversky & Kahneman, 1973) suggests that individuals may rely too heavily on the first piece of information they encounter, even if that information is incorrect. AI-generated content can exploit this bias by presenting initial falsehoods in ways that are difficult to dislodge.

Nudge Theory and Misinformation

One interesting concept in behavioral economics is nudge theory, which suggests that subtle changes in the environment can influence people's decisions without limiting their freedom of choice (Thaler & Sunstein, 2008). In the context of AI misinformation, nudging could involve presenting information in ways that encourage users to verify content before sharing it.

For example, social media platforms could nudge users by incorporating AI-powered tools that flag potentially misleading content, or by providing links to fact-checking websites. By making these tools easily accessible and non-intrusive, platforms can encourage users to engage in more responsible information-sharing practices.

Combatting AI Misinformation: Habits-Focused Strategies

The article advocates for habits-focused strategies to combat AI misinformation. These strategies focus on developing long-term habits that empower users to recognize and reject misinformation.

1. Promoting Media Literacy Education

As mentioned earlier, integrating media literacy education into schools and public awareness campaigns is vital. However, this education must be ongoing and adaptive. The landscape of AI and misinformation is constantly evolving, and so must the educational tools designed to counteract it. AI-powered simulations, for example, could be used to train users on how to identify deepfakes or AI-manipulated text.

2. Encouraging Verification Habits

Encouraging individuals to verify the information they encounter before sharing it is another crucial habit. This can be achieved through the use of fact-checking websites, reverse image search tools, and other AI-based verification technologies. Making these tools more accessible and integrating them into everyday platforms can nudge individuals to adopt verification as part of their regular online habits.

3. Building Skepticism and Healthy Distrust

Skepticism plays a critical role in mitigating the effects of AI misinformation. However, this skepticism must be paired with active engagement. Passive skepticism, where individuals merely doubt the truth of information without taking any action, is not sufficient. Instead, individuals must actively verify information before accepting or sharing it. This is where media literacy and verification tools come into play.

4. Collaboration Across Stakeholders

Fighting AI misinformation is not the responsibility of any one group but requires a coordinated effort from governments, technology companies, and individuals. Governments can create regulatory frameworks to hold companies accountable for the spread of AI misinformation, while technology companies can develop AI-powered tools to detect and flag manipulated content. Collaboration between researchers, educators, and tech developers is essential to ensure that solutions are both effective and scalable.

Conclusion

The integration of thematic analysis with desk research reveals complex dynamics in how individuals perceive and interact with AI-enabled misinformation. Psychological and behavioral economics theories provide a framework for understanding these behaviors and attitudes. However, addressing these challenges requires a combination of critical thinking, skepticism, and active engagement in the fight against misinformation.

Key insights from the analysis include:

Heuristic reliance is insufficient against sophisticated AI misinformation.

Varied concern levels do not necessarily protect individuals from vulnerability.

Education and media literacy are critical in empowering users to critically evaluate content.

Acceptance of AI's benefits must be balanced with awareness of its risks.

Traditional detection strategies may fail against advanced manipulations.

Skepticism alone is inadequate without deeper engagement and verification.

Erosion of trust in media sources can undermine societal structures.

Collaborative approaches are essential to effectively combat misinformation.

These insights underscore the importance of a coordinated effort that combines technological solutions, regulatory frameworks, and educational initiatives to build a more resilient and informed society. Along with these insights, implementing practical strategies for combating misinformation can further enhance the effectiveness of these efforts.

Practical Guide for Combating AI Misinformation

To help individuals discern misinformation and take action, here’s a set of strategies grouped by ease of implementation:

Quick and Easy Strategies

Pause Before Reacting: Take a moment to reflect before accepting emotionally charged content.

Practice Healthy Skepticism: Question the validity of information, even from trusted sources.

Double-Check with Multiple Sources: Verify information from at least two reputable outlets.

Consult Fact-Checking Websites: Use Snopes or FactCheck.org to verify viral content.

Engage in Thoughtful Discussion: Discuss controversial topics with others to gain perspective.

Report Suspicious Content: Flag misleading information on social media platforms.

Control Your Exposure: Adjust your social media settings to limit unverified content.

Moderate-Effort Strategies

Create a Verification Routine: Spend a few minutes checking the authenticity of news before sharing.

Use Tools for Verification: Learn to use reverse image search and fact-checking tools.

Strengthen Critical Thinking: Regularly question the logic behind information.

Curate Your Sources: Follow only reputable outlets and unsubscribe from unreliable sources.

Stay Informed on AI Trends: Keep up with how AI is being used to create misinformation.

Adjust Content Settings: Customize your social media to reduce exposure to unreliable sources.

Higher-Effort Strategies

Invest in Ongoing Education: Take courses and read materials on misinformation and media literacy.

Teach Others About Misinformation: Share knowledge with your community to spread awareness.

Support Media Literacy Initiatives: Advocate for media literacy programs in schools and workplaces.

Leverage Technology for Detection: Use browser extensions and tools to identify fake news.

Engage in Collective Efforts: Join or support organizations focused on combating misinformation.

Promote Fact-Checking and Accountability: Support fact-checking initiatives and hold sources accountable.

Understanding these insights and applying these practical strategies are vital for mitigating the risks posed by AI-enabled misinformation. This combined approach—grounded in both technological solutions and educational efforts—will help foster a more informed, resilient society, capable of effectively navigating the complexities of the digital age.

References

Bandura, A. (1977). Social Learning Theory. Prentice Hall.

Begg, I. M., Anas, A., & Farinacci, S. (1992). Dissociation of Processes in Belief: Source Recollection, Statement Familiarity, and the Illusion of Truth. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 121(4), 446–458.

Cappella, J. N., & Jamieson, K. H. (1997). Spiral of Cynicism: The Press and the Public Good. Oxford University Press.

Chaiken, S. (1980). Heuristic Versus Systematic Information Processing and the Use of Source Versus Message Cues in Persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(5), 752–766.

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340.

Davison, W. P. (1983). The Third-Person Effect in Communication. Public Opinion Quarterly, 47(1), 1–15.

Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and Unaware of It. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1121–1134.

Moore, D. A., & Healy, P. J. (2008). The Trouble with Overconfidence. Psychological Review, 115(2), 502–517.

Nickerson, R. S. (1998). Confirmation Bias: A Ubiquitous Phenomenon in Many Guises. Review of General Psychology, 2(2), 175–220.

Olson, M. (1965). The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups. Harvard University Press.

Peltzman, S. (1975). The Effects of Automobile Safety Regulation. Journal of Political Economy, 83(4), 677–725.

Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1986). The Elaboration Likelihood Model of Persuasion. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 19, 123–205.

Rozenblit, L., & Keil, F. (2002). The Misunderstood Limits of Folk Science: An Illusion of Explanatory Depth. Cognitive Science, 26(5), 521–562.

Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive Load During Problem Solving: Effects on Learning. Cognitive Science, 12(2), 257–285.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1973). Availability: A Heuristic for Judging Frequency and Probability. Cognitive Psychology, 5(2), 207–232.

Weinstein, N. D. (1980). Unrealistic Optimism About Future Life Events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(5), 806–820.

Comments